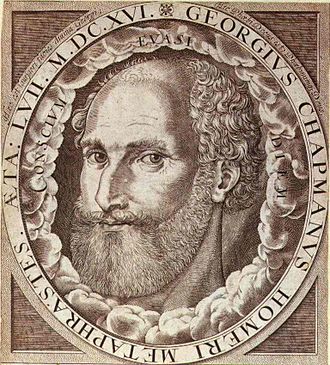

George Chapman was born in Hitchin, England in 1559, and died in London in 1634. He was a great English poet and playwright. He was a man of letters and very erudite, with a perfect knowledge of Greek and Latin. Thus, he started on a considerable work, creating a translation of Homer’s works. He was the first translator of Homer into English, after Arthur Hall (1539-1605) and his partial translation of the first ten songs of the Iliad. Chapman has a singular vision of translation. Indeed, he thinks that knowledge was known to the ancients, to what are commonly called wise men, old people who possess it and who spread it orally and in writing to young people. It is translation that shares the knowledge with individuals in order to instruct them. There is also the desire to see them discover a completely different culture.

Source: Internet Archive

Chapman translation is particularly good at conveying both breadth and depth, he can move from sensitive emotional perceptions to drama. In Chapman’s Homer, we can read in the preface the following sentence, saying that Chapman is able to “follow Homer in endowing the everyday world the heroes inhabit with a sheen of graceful materiality – every spear, every ship is described as special in its utility, every tree or animal vivid in its particularity[1].” The most important thing to remember is that it is not possible to have a perfect translation, except the one that the reader can have in mind. But George Chapman uses the preface to break down his work as a translator and to explain the necessary path of his work. Firstly, he explains that his creation, unlike Arthur Hall’s, who recognised that his translation came from French and was therefore a translation of a translated text, uses the original Greek text as its source. Nevertheless, he used a Latin text, a Greek-Latin edition by Jean de Sponde, published in Basel in 1583. This is a very interesting book, which we have already dealt with in a video as part of the master’s programme, and which can be found in the Besançon municipal library.

As for Chapman, he does not see the problem of establishing a non-literal translation. Indeed, he made a real philosophical link with it. According to him, it is a passage from one country to another, it is ‘naturalized’ and takes part in its new country. If an individual obtains another nationality, he or she is likely to adapt a little to the customs of the country. For Chapman’s translation, this is exactly how it should act. He analyses the source text, works with it, and translates it, adapting the form of the words. He creates a real harmony, and provides the consequent work of the poet, unlike a classical translator who looks like one but is not. Chapman establishes three stages: first, the naturalization of the text, then its modification, and finally its reception by the reader. But the poet takes his idea much further, he believes in the synchronisation between two poets, which the text mediates. Thus, he expresses the feeling that he is bringing Homer to life through English and therefore rewriting the work as if it were the first time. He does not vulgarise the translation, on the contrary, he sublimates it, giving it depth and poetry. No, it is in no way a perdition if someone takes the trouble to make it become alive.

[1] Chapman’s Homer, The Iliad and the Odyssey, George Chapman, Wordsworth Edition, Hertfordshire, 2000.